Our backs were against the wall

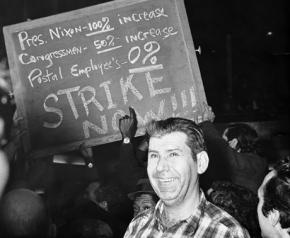

Beginning in the mid-1960s, public-sector workers influenced by the Black Power and antiwar movements brought that militancy to their workplaces. Even though strikes by public employees were illegal, workers walked out anyway in wildcat work action. One of the outstanding wildcats of the time was a strike by postal workers in 1970.

was a leader of the 1970 wildcat strike in New York. In July, Lee spoke on a panel discussion "Wildcat! The 1970 postal workers' strike" along with Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor at the Socialism 2011 conference in Chicago. Here, we reprint Tara's Lee's speech.

I'VE BEEN introduced as a postal worker, a radical and a leader of a wildcat strike--and I did that before my 22nd birthday. God, what the hell have I done in the 41 years since? I'm going to give you a little bit of history of what happened with the postal workers that led up to the strike.

The postal workers first started getting hit with wage decreases back in the Depression of the 1930s because one of the things we had back then was the beginning of Keynesian economics and "pump priming" and everything--except when it came to government workers, who took a 25 percent pay cut under Franklin Roosevelt by executive order. At that time, we had no union and things were done by executive order or acts of Congress pertaining to postal workers and every other government workers.

So right away, we are 25 percent behind the rest of the population. And throughout the remaining 30-plus years until we had our strike, we continued to fall behind because the only way back then that a postal worker got a raise was through an act of Congress.

We had no union, and we had no collective bargaining agreements, none of that. A postal worker could be fired if the postmaster didn't like the way they looked. That was it. There was nothing we could do. There was no contract, no negotiating, no bargaining rights, nothing.

So 1970 comes, and we're falling way behind in wages. Eisenhower had vetoed two pay raises for us during his presidency, Kennedy had passed one. I got a big raise of 9 cents the first year I worked there, and I went from $2.95 an hour to $3.04 an hour. It took 21 years to reach top pay, which was $8,800 a year. Consider that in metropolitan areas--people living on $8,800 a year trying to raise a family of four or five. You just couldn't do that.

There was no way that Congress was going to pass a pay raise for us at that time. We had the Vietnam War and the failed War on Poverty, and we had massive budget deficits. It was almost like the situation today--not as bad economically, but where we were trying to have an austerity budget, , cut federal spending, do away with the "waste" from the War on Poverty, get rid of all those programs that were helping people because we were wasting too much money in Vietnam.

Tara Lee and Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor talked about the history of the illegal 1970 wildcat strike of postal workers at a meeting at the Socialism 2011 conference in Chicago in July.The 1970 postal wildcat

I guess over the last 40 years, this country hasn't learned anything either. Well, not the country, but the people in charge of it. We've learned something--that's why we're here.

I BECAME a strike leader, mostly through default, because nobody else had the courage to stand up to do so. New Rochelle, where I was working at the time, was a small suburban city just north of New York City. Our strike started on March 17, 1970, St Patrick's Day.

New York City Branch 36--God bless them--passed a resolution to go on strike. That's right. It was started by a postal worker by the name of Vince Sombrotto. In 1978, Vince Sombrotto was elected president of the National Association of Letter Carriers, and he won by a huge margin. He won on the issue that in 1978, we were offered a contract with a cap on it--and when I say "cap," I mean a cap on wages, a cap on our cost-of-living increases.

Our national president at that time, Joe Vacca, from Cleveland, accepted it, and the rank and file voted it down and told him to go back and renegotiate. He did. It was too late for him. We voted him out of office. Vince Sombrotto became president, and he was president of our union for close to 30 years after that.

In 1970, though, he was just a regular city carrier in New York City. He made the motion to go on strike, and it carried. Branch 36 went out on strike March 17, 1970. A succession of little branches around New York City and on Long Island followed. Also in New Jersey, Newark, Teaneck and a couple of the other big cities went out. Bridgeport went out, New Haven went out, Hartford when out, and it spread up through New England--Boston, Providence, all the major cities in New England went out and some subsidiary localities around them.

Philadelphia and Pittsburgh went out, and it mushroomed throughout there--Allentown, Pennsylvania, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, and we moved westward to Minneapolis and to the West Coast. Los Angeles went out, San Francisco went out, Portland went out, Sacramento went out, Seattle went out.

You notice, I'm omitting the South. Not one branch from the South went on strike.

When we went out, it was like mass confusion. They were going to break the strike, so they called in the National Guard. Well, you can call in the National Guard and the reserves to try to deliver the mail, but if you don't have the training to know how to do it, you're not going to deliver the mail. There's no way.

And here's the best part about it. We had a secret weapon: a lot of postal workers were veterans. A lot of them were in the National Guard and the reserves. And they had been in since the Second World War or the Korean War. So they were high up. So they would go through the people who came in, and they would tell them how to screw up the mail. So we made sure no mail got delivered.

I have to say some words about the people who went out. I was 21-and-a-half years old when I got hired. I could have been a bartender, driven a cab, done whatever. I was going to school at the time. I figured I'd get out of school, get a degree and quit the Post Office. Well, I never did. I just stayed there because economic conditions up North and our raises that we got from the strike made it worth my while to stay there.

But these guys went out on strike then, and it was illegal. We all could have been prosecuted, and we all could have been arrested--every single one of us. We all could have lost our jobs. What they risked was their pensions, their homes, everything they had. And they did so, because we were pushed against the wall.

We didn't have a choice. We had people in the big cities who were collecting welfare because they had a family of four or five, and they were living below the poverty level. We just had our backs up against the wall.

OUR NATIONAL president ordered us back to work. We didn't go back. That's what made it a wildcat, because it was not a legal strike. It never was a legal strike, period.

We did try to negotiate. I know nobody here really likes Richard Nixon too much of course, but I have to say, unlike Ronald Reagan, who 11 years later fired the air traffic controllers, Nixon realized that things were wrong. He had tried to get through Congress a Postal Reorganization Act, which would have given us a certain measure of collective bargaining, but it was stalled.

The reason it was stalled was simply because of political patronage. In the old system, if a Democrat was elected president, in every city in the country, in every town in the country, we had a new postmaster. He usually was the head of the local Democratic Party or someone that they recommended.

If the Republicans won, then we had Republican postmasters. They didn't know a damn thing about the Post Office. The assistant postmaster was the person who ran everything. It was the career guy who worked himself up and knew how the mail system worked.

Our postmaster in New Rochelle was the town clerk before he was made postmaster. You want to talk about somebody from the Sopranos? He walked around with a cigar in his mouth like this, and he'd give his big pep talk: "I've been the number one postmaster around here in this region for five years in a row. I fired 150 people to get there, and if I have to fire another 150 people this year to be the number one postmaster again, I'm going to fire 150 people. Now get back to work."

When the Postal Reorganization Act went into effect [as a result of the strike], we automatically got a pay raise and step increases going back retroactively for a year. So we got a nice big lump sum---one payment. The Postal Reorganization Act did away with the patronage system. Then we had career people coming in and taking over as postmasters, people who worked their way up and knew what they were doing.

Our mail service improved. Our wages drastically improved. I'll give you a little example. Back in 1968 when I started, my pay was $118 a week based on a 40-hour week, which came out to a little over $6,100 a year. When I retired in 2003, I was making a little over $42,000 a year, which is pretty good. I could live comfortably on that salary. I could raise a family. We could take vacations. We could have a nice house. It's what American working people should have who do a good job.

Our work is not easy. Our work is pretty hard. I walked 10 to 12 miles a day for more than 30 years. I've got arthritis and I've got curvature of the spine from that. It happens. People have carpal tunnel from continuously putting mail into a mailbox. It happens.

We go around and we deliver mail in all kinds of weather. I've delivered mail when it was 10 degrees below zero in New York, and I've delivered it when it's been over 100 degrees in Florida, after I transferred there. I've delivered it in hurricanes and in blizzards. So it is a physical job; it's not an easy job. But it's a good job because I had a good rapport with the customers on my route. I was friendly with them.

The most important thing we had to do was get ourselves in a position where we had the same rights as every other union. At that time, we were an association. We weren't allowed to call ourselves a union. And we're still the National Association of Letter Carriers, because we honored our past by not taking the name "union" when we could.

The Postal Reorganization Act compressed the wage scale from 21 years to eight years, which I think is still too long for someone to reach top pay. And in contract negotiations since then, it's gone back up to 13 years. Like all other things these days, it's going the wrong way for labor.

We don't have the right to strike. The Postal Reorganization Act set up a mediation and arbitration system if you had a contract impasse, and this was at the local level also, with local negotiations concerning rotating days off or fixed days off for carrier schedules, because we do have six-day delivery still. It set up vacation schedules and how many people can take off in what they call "prime time" during the summer months.

So we have these negotiations at the local level as well as the national level on safety and health, on wages, length of time to get top pay, how many sick days we get, vacation time, all those things.

IT GAVE us a collective bargaining agreement. And that was the most important thing that we got out of the postal workers' strike. Yes, the wages were great at the time, but we got a collective bargaining agreement and a contract, and people could no longer be fired at the whim of management.

Management felt that they were dictatorial and they could do anything they wanted to, and they used to break the contract left and right by giving us a legal order. And as shop steward, I used to walk around with a copy of the contract in my pocket, pull it out and turn to whatever page I needed and say, "You can't do that. It's right here--see it's against the contract." They didn't like me too much.

In that respect, we won. We won big. We got what we wanted. We got a collective bargaining agreement. We got wage increases. We got a condensed level to top pay. We did well. And the reason we did well was because we had the support of the people.

The people know their mailman. They like their mailman most of the time. They see their mailman every single day. You know, they're mailing a letter: "Can you take this for me, mailman?" I was on the same route for 10 years. Everybody knew me. In most cases, that's the way it is.

We had the respect of the people, and we had the people on our side. And that's what we need to do today to win again. We need to show the faces of the American labor movement out there to the public so that people will know that the American labor movement is working for them, that we're not against them. When we do services for the people, we need to let them know that we're union.

That's extremely important. With the right wing's attack against labor, I think in a lot of cases, people don't know that anymore. So they have to get re-educated to a certain degree that the worker, the laborer, the union man is working for me. He's building the products that I'm going to use. And that's very important.

It's also very important that we have a working class that makes a good wage, that's treated with respect. Because look at what's happened. Our purchasing power has decreased, and we can't buy the goods and services that are being made. So nobody is producing more goods and services; we're still left with the ones they made three years ago.

And when that happens, because people's jobs are outsourced, we can't buy the products that we need to buy to keep manufacturing going. So manufacturers lose money and they go out of business, and our people lose jobs. It's a vicious cycle, and it needs to stop.

I was very proud to have a part in our strike. The fear of being arrested back then scared a lot of people. I remember our local president at the time. He stood up at our meeting and he was like this: "This is a court injunction. They're going to lock me up if we go on strike." And we looked at him and said, "Well, the only thing you're good for is organizing the picnic every year anyway, so."

So I made a motion that we go out on strike and honor the strike that Branch 36 had started and set up picketing and the whole nine yards. The motion was seconded, we had a little bit of a debate, it passed, and the next day we had a picket line in front of the post office.

It was great. I totally loved that. Wildcat strikes can work. That proves it. We just have to get back to our roots and have the American labor movement get fired up again and do what they need to do--take action and defend themselves, because that's what we did.

Our backs were to the wall. We had to do it. And when you put people with their backs up against the wall, they will take desperate actions--because you've made them desperate people. I can't say enough about the people who went on strike, the older people back then, because they were very courageous.

Transcription by Karen Domínguez Burke