Doing the math about class size and inequality

Class size is at the heart of the Portland teachers' contract fight and the struggle for education justice--but school officials have another agenda. explains.

THE PACIFIC Educational Group (PEG) markets its "Courageous Conversations" program as "a protocol for engaging, sustaining and deepening dialogue about race, and an essential tool for effectively examining schooling and improving student achievement."

In answer to the question "Why explore race?" PEG's website continues: "Race matters--in society and in our schools. It is critical for educators to address racial issues in order to uncover personal and institutional biases that prevent students of color and American Indian students from reaching their fullest potential. Courageous Conversations serves as the essential strategy for school systems and other educational organizations to address racial disparities through safe, authentic, and effective cross-racial dialogue."

Since 2007, Portland Public Schools (PPS) has spent over $2.5 million on this employee training program, and the district has plans to spend another $1 million a year to fund its own equity office based largely around these ideas. About half of $2.5 million has gone directly to PEG--the rest was spent on travel and related costs for teachers and administrators to attend conferences in San Antonio, Texas, and San Francisco.

What seems to be missing, however, from PEG's program and PPS's participation in it is a commitment to actually doing anything about the "institutional biases" PEG talks about.

When PPS Superintendent Carole Smith is lauded for her "commitment to improving equity of access and equity of results for all students" based on her commitment to the Courageous Conversations program, we should be asking whether "conversations" and "dialogues" are the best way to achieve this goal.

And when PPS's program of choice--on which it has spent millions of dollars, and plans to spend millions more--turns out to have produced results that are questionable, if not downright failing, we need to be looking at alternative ways to address inequality in Portland schools.

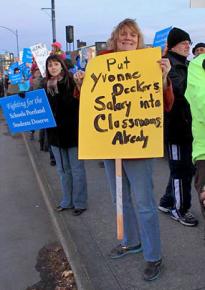

Like reducing class sizes--one of the central issues in the battle between PPS and the Portland Association of Teachers (PAT). A teachers strike is looming on February 20 over the union's demands for a contract that addresses not only their working conditions, but the learning conditions for all their students.

MULTIPLE STUDIES (here and here, for example) have shown that while reducing class size has a positive effect on all students in every way that can be measured--including improved grades, improved attendance and higher test scores--it has a disproportionately positive effect on minority and low-income students.

One Princeton University study concluded that class size reduction is "one of very few educational interventions that have been proven to narrow the achievement gap." For example, the Princeton researchers found that attending what they classified as small-sized classes, compared to regular-sized classes:

raises the likelihood that Black students take the ACT or SAT college entrance exam from 31.8 to 41.3 percent, and raises the likelihood that white students take one of the exams from 44.7 to 46.4 percent. As a consequence, if all students were assigned to a small class, the Black-white gap in taking a college entrance exam would fall by an estimated 60 percent."

Further, the studies conclude that the disproportionate benefits of reduced class size for minority students extend beyond academic achievement, such as improved reading and math test scores, to broader social criteria--for instance, Black teenage males who attended small-sized classes were 40 percent less likely to become fathers at a young age, compared to their peers in regular-sized classes.

And yet, while minority students are the most likely to benefit from smaller class sizes, research also shows that they are the least likely to be in these classes. For example, in one study on reducing class size, researcher Douglas D. Ready reported:

[T]he burden of large kindergarten and first grade classrooms [is] shouldered disproportionately by children of color...For instance, while non-Asian minority groups constitute about a third of all kindergarten and 1st grade students, they account for almost half of the children attending public schools with kindergarten and 1st grade classes larger than 25 students.

These studies run counter to the logic of "Courageous Conversations"--and toward the inescapable conclusion that the roots of racial disparity in student experience and achievement are material, not a matter of "dialogue."

Addressing the issue of inequality in schools requires more than "conversations" among individual teachers and administrators. It's the "institutional biases" that lead to schools being treated differently in terms of resources that need to be courageously confronted.

IN PORTLAND, you don't have to look very far to see the problem.

Schools in the Jefferson cluster--located in the city's historically Black North Portland area, the site of the only majority-Black high school in the state, with 75 percent of students on free or reduced lunch--have consistently underfunded, closed down or "restructured" through market-based strategies based on the idea of "school choice."

In the last 10 years, the Jefferson cluster has seen more schools closed than the rest of the PPS clusters combined--so obviously, this cluster's students and families have disproportionately suffered disruptions to their educational experiences.

Schools in the cluster are systematically underfunded--and then declared "failing" by the district. This leads to a downward cycle: Transfer policies allow families who can manage to do so to put their children in other schools, which leads the district to pull more money out of the "failing" schools as enrollment goes down. The students left behind often attend classes with over 40 students--or in other cases, can't get into the classes they need to graduate after teacher positions and entire programs are slashed.

The same students who are being left with the least are the ones who are most in need of schools with adequate educational resources. As Jefferson sophomore Sekai Edwards explained in an interview with KBOO's More Talk Radio show:

[This is where] you have low-income families, where parents are probably working two or three jobs, and they might not be able to come home and sit down and read with their children every night, [even though they] would probably like to. But realistically, they just don't have time to do it.

The needs don't stop with smaller class sizes and more teachers, either. Schools like those in Jefferson cluster are located in the communities most impacted by society-wide racist policies like mass incarceration, stop-and-frisk and the school-to-prison-pipeline.

If Carole Smith and PPS truly cared about the issue of educational equity, they would spend money on resources and programs that would impact minority and low-income students in the classroom--not on ones for administrators and staff to talk about how the disparities affect them.

Besides ensuring that no school is left to "fail" due to systematic underfunding, there's much more PPS could do--like fully fund programs in arts, music, theater and P.E., as well as advanced courses, so that all students are challenged and prepared for the world outside the classroom.

If the board is so committed to "equity of results," it should guarantee fully funded wrap-around services in all schools, including qualified counselors, additional academic support programs like Head Start where needed, and food and health programs--to make sure that kids' needs are met as much as possible before they enter the classroom.

These are the kind of programs and policies that could help "all students, especially students of color...[to] reach their fullest potential," as PEG claims for its "Courageous Conversations" program.

And these are the kinds of programs and policies that won't come from the district making a deal with the PEG, but with the Portland Association of Teachers, which called for all this and more in its contract proposal entitled "The Schools Portland Students Deserve."

When the research shows that reducing class size is the easiest, most effective way to raise achievement of all students and diminish the racial achievement gap; and when the PAT has made it clear with its proposals in contract negotiations that the district can afford to do exactly this; then you have to ask the question: Why won't PPS at least take this easy step toward making our schools better and more equal?

In his speech on "Still Separate, Still Unequal: Racism, Class and the Attack on Public Education," New York City educator Brian Jones provides the ugly answer:

If you had all the ideas of what we could do about education, you could put them into two piles...On the one hand, you would put all the ideas about how to reform schools and education that might have the side effect of strengthening the labor movement. And on the other hand, you would put all the reforms and ideas that would weaken or hurt it.

Jones' point: Small class sizes means more teachers, and more teachers means a potentially stronger teachers' union. That's exactly what Carole Smith and PPS, which represent the interests Portland's elite, not its working majority, don't want to see.

As Jones continues:

[W]hat we have is almost like a labor policy masquerading as an education policy, an economic policy about attacking labor and the unions and the working class as a class of people masquerading as a pedagogical strategy to improve instruction. Because really, we know that the things that have the most research behind them, the things that are obvious, the things the rich people are already doing for their own kids, are the things that they are refusing to do for our students.

As the contradictions between what the school board claims it wants to do and what it actually does become more glaring, Portland students, parents and communities are coming to see all the more clearly that the Portland teachers' union is on their side in the struggle for education justice.

The PAT's struggle for a just contract is the best defense against corporate interests that would like to see public education turned into something that benefits them--be it through selling consulting services on promoting dialogues about race, or hawking test prep books, or funneling public money into private charter schools, or simply turning out the next generation of low-wage workers--rather than the students who go to these schools.

This is why communities in Portland, Medford and other cities across the country are standing behind the teachers who are righting better working conditions and students' learning conditions.

We know that this isn't just about them. It's about all of us.