The workers’ movement that led to May Day

Is the call for a general strike on May Day this year in keeping with the traditions of the working-class holiday? examines the history for the answer.

MAY DAY is an international working-class holiday that originated in the U.S., but until recently was celebrated by few people in this country.

That changed starting in 2006, when a mass immigrant rights movement used May 1 as a national day of action to demonstrate for justice.

This year, May Day has a further resonance, coming after the rise of the Occupy movement that galvanized anger at the greed and power of the 1 percent. Activities this year can seek to draw in the people brought into political activity by Occupy and to deepen the renewed interest in the rich tradition of working-class struggle in the U.S.

But among activists, there are different ideas about what May Day should mean. Some local movements are organizing around a call for a "general strike" on May 1. In reality, this won't be an actual general strike--a coordinated action by workers to stop production--but individual acts of protest, ranging from calling in sick at work to boycotting stores and other businesses.

This risks making the idea of strike action less meaningful, at a time when labor activists should be trying to revive the concept as a weapon in the struggle against the employers. Worse still, some anarchist activists are planning confrontational direct actions that seem designed to emphasize their distance from wider layers of people.

The debate over a "general strike" on May Day is bound up with a broader issue of the relationship of the Occupy movement to traditional working-class organizations--most importantly, unions.

Many of the activists leading the call for a general strike explicitly view unions as the preserve of "privileged" workers. This is exemplified by a slogan adopted by some West Coast radicals that the Occupy movement represents not the 99 percent, but the 89 percent--that is, the "non-privileged" workers who are not organized into unions.

Both the broader conception that unions represent a "privileged elite" and the specific calls for a general strike will make it harder for the Occupy movement to use May Day as an opportunity to build a stronger connection to workers and labor. If these ideas prevail, May Day will be relegated to the actions of a self-selected few.

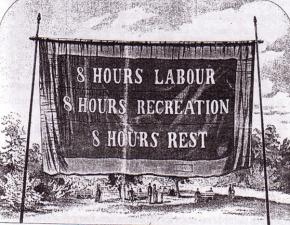

This whole approach neglects the actual history of May Day. May 1 is the anniversary of a real general strike for the eight-hour day in 1886, involving hundreds of thousands of workers across the U.S. And the Haymarket Martyrs, who were framed and sentenced to death following the general strike, were anarchists and socialists who were intimately involved in the labor movement of their time, as part of the larger working-class struggle for a just society.

THE FIRST May Day in 1886 was the culmination of a massive organizing campaign for a concrete demand that won the backing of tens of thousands of workers. The demand for the eight-hour day emerged from the factories, packinghouses and rail yards where workers regularly suffered through workdays longer than 14 hours.

The demand wasn't a new one--there had been an eight-hour campaign 20 years before. Actually, many states had eight-hour day laws on the books, but they weren't enforced, and bosses could use various loopholes to avoid adhering to them. Politicians, even some who claimed support for the eight-hour demand, looked the other way.

It was becoming clear that workers would have to organize themselves to make the eight-hour demand a reality in their workplaces.

There were debates among radicals at the time about whether the eight-hour demand even deserved their support--some thought it didn't go far enough or get at the heart of the real problem of capitalism. But many other socialists and anarchists, like Haymarket Martyrs Albert Parsons and August Spies, threw themselves into the demand for the eight-hour day and pulled other radicals behind them. They helped make Chicago the epicenter of the struggle.

Along with Spies, Parsons--who described himself as an anarchist, communist and socialist--helped found the International Working People's Association (IWPA) in Chicago, which gained a significant base in the city's radical immigrant communities.

The Chicago group diverged from other such clubs around the country because--while agreeing that political action was futile and seeing the value in the use of force--it recongized the importance of trade union organization. This combination of anarchist principles and trade union activity became known as the "Chicago idea."

At first, the IWPA didn't support the eight-hour demand, declaring in its newspaper The Alarm, "To accede the point that capitalists have the right to eight hours of our labor is more than a compromise, it is a virtual concession that the wage system is right."

But when IWPA leaders saw how it inspired workers to take action, they changed their mind. Parsons explained that the group endorsed the eight-hour demand, "first, because it was a class movement against domination, therefore historical, and evolutionary, and necessary; and secondly, because we did not choose to stand aloof and be misunderstood by our fellow workers."

There were also debates among leaders of organized labor at the time over the eight-hour demand how to achieve it. The leaders of the largest working-class organization at the time, the Knights of Labor, supported the demand, but refused to back more militant methods of organizing for it, like striking--favoring instead methods such as letter-writing campaigns.

Despite this, however, members of the Knights of Labor--many of whom had joined during a huge rail strike the year before--organized walkouts and other local actions to press for the eight-hour day.

The spreading workers' sentiment compelled a smaller union organization, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions--which would later become the American Federation of Labor--to not only endorse the movement but call for a general strike on May 1.

In preparation for the May 1 general strike, organizers reached out to workplaces everywhere. Workers could show what side they were on by wearing "eight-hour shoes," smoking "eight-hour tobacco" and singing the "eight-hour song."

As labor historian Philip Foner writes: "[T]housands of workers, skilled and unskilled, men and women, Negro and white, native and immigrant, were drawn into the struggle for the shorter workweek." By mid-April 1886, Foner wrote, "Almost a quarter of a million industrial workers were involved in the movement, and so powerful was the upsurge that about 30,000 workers had already been granted a nine- or eight-hour day."

Workers organized in their workplaces to prepare for the coming strike, and on that day, some 190,000 workers walked out around the country. The preparation for a walkout was so great that the threat of the strike won the eight-hour demand for tens of thousands of workers before it even began.

THE INCIDENT in Chicago's Haymarket Square represented a recognition by the bosses and the government that the workers' movement had to be crushed, brutally and decisively.

Police had led an attack on strikers on a picket line on the city's South Side, and a rally was called for Haymarket to protest the attack. The demonstration was nearly over when police started advancing on the crowd. A bomb was thrown into the ranks of the police--it is still unknown by who.

Leaders of the Chicago labor movement were blamed for the death of police, even though the state never connected any of the eight to the bombing. Prosecutors played on the image of the bomb-throwing anarchist to vilify the working-class leaders and win death sentences against seven of them. On November 11, 1887, Parsons, Spies and two others were hung. Louis Lingg cheated the hangman by committing suicide the night before.

The Haymarket Martyrs are part of the rich tradition of the U.S. working-class movement. In looking back on their history, it's important to recognize that these leaders of the eight-hour movement didn't view themselves as enlightened activists whose individual actions would set workers in motion. They involved themselves in a mass working-class movement, whose united action on May 1, 1886, showed the power workers have when they organize to struggle collectively.

May Day 2012 is an opportunity to strengthen the connections between unions and Occupy, and help rebuild some of the power demonstrated last fall, especially in New York City, when the labor movement called out its forces to defend Occupy Wall Street.

As a call by Occupy Chicago puts forward, May Day should be a day of action for the 99 percent--in which activists continue the concrete struggles taking place in every city, against foreclosures, police brutality, school privatizations and much more.

And May Day should be used to recapture the lessons of the struggles of the past--for a new generation of activists to put them to use in a movement for a better future.