Nothing can be changed until it is faced

The new documentary I Am Not Your Negro uses writer James Baldwin's remarkable voice to tell the story of the Black freedom struggle. has a review.

DO YOURSELF a favor: Figure out now when and where you can see the new documentary I Am Not Your Negro, and don't let anything short of another mass protest against Trump stop you from going.

You need to see this movie, and not only because it's a valuable contribution to the discussion of race and racism in the U.S., with insights that can help anti-racists know what to say and do in the struggle today.

You need this movie to heal your mind and soul from the foul experience of the Trump presidency--cleanse them of the ugliness that accumulates and weighs you down from each time you heard his shrill tirades or watched his strutting displays of arrogance and hate.

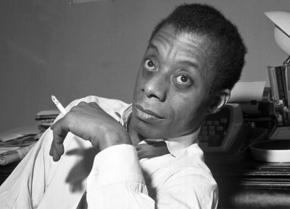

As an antidote to Trump's poison, you need a strong dose of his opposite in every possible way: James Baldwin, one of the greatest writers and speakers in U.S. history, one of its most brilliant minds, and one of the most powerful voices in the struggle for racial and social justice during the second half of the 20th century.

I AM Not Your Negro is built around Baldwin's words, woven together from several sources to tell a kind of personalized history of the Black struggle in America, with particular emphasis on the civil rights and Black Power era.

There are no talking-head commentators in this documentary, only Baldwin's own voice as he bitterly lays bare racism in America and its consequences at every level, from socio-economic to brutally personal and psychological.

Baldwin himself appears onscreen in clips from various television appearances and speeches caught on film, but the guts of the movie are passages from an unfinished writing project, read by Samuel L. Jackson.

In 1979, Baldwin began a long-form essay, to be called Remember This House, about three martyrs of the struggle who he knew and loved: Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King.

He only finished 30 pages, but as brought to the screen by filmmaker Raoul Peck, the unfinished essay rises to the challenge of explaining the dynamics of race and the urgency of confronting racism in a country that questioned--even in the 1960s, while Jim Crow segregation still lived--whether racism needed to be confronted.

Baldwin was especially skilled at answering that question, drawing not only on his own experiences living in a racist society, but from the unique vantage point of being a celebrated writer, some steps remove from the front lines of the battle.

Baldwin gained fame as a novelist. His celebrated first book Go Tell It on the Mountain was a blistering examination of a Black family crushed by poverty, discrimination and the stifling embrace of religion. His next novels, Giovanni's Room and Another Country, broke ground in putting LGBT sexuality at the heart of their stories--they also defied expectations by dealing largely with white characters.

These books established Baldwin among the new generation of American writers emerging after the Second World War, but they also set him apart from the kind of books expected of a Black writer. Though very much influenced by left ideas, Baldwin personally strove to distinguish his work from what he called the "protest novels" of the most famous African American novelist of the time, Richard Wright.

That wasn't fair to Wright--nor, actually, to Baldwin's own writing. But in any case, his desire to remain detached couldn't last long--because of the impact of the struggle.

A passage from Remember This House describes how film footage of the Little Rock school desegregation battles drew Baldwin back from a writers' life in Paris. "It's very difficult to sit in front of a typewriter and concentrate on that," he said, "when you're afraid of the world around you."

FROM THIS point on, Baldwin became better known for his essays and journalism than his fiction writing. But as the documentary recounts, Baldwin, though a fierce advocate for the struggle, understood that he would best serve the movement as an observer, rather than an organizer--ready to bear witness to the twisted, irrational and deadly effects of discrimination.

In a speech to the famous Cambridge Union debating society in England--where he was received with an unprecedented standing ovation--Baldwin describes in the simplest terms the "shock" of first understanding that skin color has massive, far-reaching, world-changing consequences:

It comes as a great shock to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everyone else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock, around the age of five or six or seven, to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper--that the Indians were you.

It comes as a great shock to discover the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and identity, has not in its whole system of reality, evolved any place for you.

This wasn't a message about the crude racism of the Jim Crow Southern terrorists that white liberals could nod along with. Again and again, Baldwin explained how the whole fabric of U.S. society, North and South, was infected with inhumanity and discrimination, from its political establishment to its popular culture.

Commenting on the images of violence meted out against civil rights demonstrators in Birmingham, Alabama, Baldwin insisted on drawing out the larger lesson:

White people are astounded [by the images from Birmingham], Black people are not. White people are continually asking to be assured that this is happening on Mars. They don't want to know that it is everywhere. There isn't one step morally between Birmingham and Los Angeles.

Baldwin was also called upon to explain why the Black freedom struggle radicalized through the 1960s, and he likewise rose to the occasion:

If we were white, if we were Irish, if we were Jewish, if we were Poles...our heroes would be your heroes, too, Nat Turner would be a hero instead of a threat, Malcolm X might still be alive. Everyone is very proud of brave little Israel...But when the Israelis pick up guns, or the Poles, or the Irish, or any white man in the world says, "Give me liberty or give me death," the entire white world applauds.

When a Black man says exactly the same thing, word for word, he is judged a criminal, and treated like one, and everything possible is done to make an example of this bad nigger so there won't be any more like him.

I AM Not Your Negro opens with a famous moment from the Dick Cavett Show, in which the popular TV talk show host asked Baldwin questions he faced so many times: Why aren't you more optimistic? Aren't things getting better?

The clip immediately brings to mind the same questions asked of those who struggle to make Black lives matter today. Peck dramatizes the connections of these moments across time with stark color photographs of protests and police repression in Ferguson, Missouri, and elsewhere. The images recall the worst brutality of the Southern racists, but bring us instantly to the present and the struggle still to be fought.

Baldwin's final words in the movie could be an answer 50 years later to the idea that the U.S. has become a "post-racial" society:

I sometimes feel it to be an absolute miracle that the entire Black population of the United States of America has not long ago succumbed to rage and paranoia. People finally say to you, in an attempt to dismiss the social reality, "But you're so bitter." Well, I may or may not be bitter, but if I were, I would have good reasons for it, chief among them that American blindness or cowardice which allows us to pretend that life presents no reasons for being bitter.

You cannot lynch me and keep me in ghettoes without becoming something monstrous yourselves. And furthermore, you give me a terrifying advantage: You never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me. Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.

See what I mean? Spend 90 minutes listening to James Baldwin tonight, and you'll feel better tomorrow morning, and many more after that.