Slavery and the Civil War

A century and a half after the opening shots of the Civil War, dispels the myths about the Southern slaveocracy and the war that liberated slaves.

IN MARCH 1861, Alexander Stephens, vice president of the newly established Confederacy in the South, expressed a simple truth about secession. Slavery, Stephens noted, "was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution."

Referring to the new Confederate government, Stephens stated, "Its cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical and moral truth."

Stephens could hardly have been any clearer: slavery caused secession and war, and the Confederacy was built to defend white supremacy. Yet many Americans today continue to believe that the Civil War came about as a conflict over taxation, tariff policy or states' rights.

In December 2010, a group of well-heeled South Carolinians gathered in Charleston for a "Secession Ball" to mark the sesquicentennial of their state's exit from the union. As partygoers strutted around in period costume--Confederate gray for the men and hoop skirts for the women--one speechmaker announced that the South had seceded "not to preserve the institution of slavery, not for glory or riches or honor, but for freedom alone."

Even prominent politicians engage in mythmaking about slavery and abolition. In the Tea Party response to President Obama's State of the Union address in January, conservative darling Michele Bachmann announced that the framers of the American Constitution "worked tirelessly until slavery was no more in the United States."

FOR GENERATIONS after the abolition of slavery, the U.S. elite clung to a vision of the antebellum South that included mint julips on the veranda, Southern belles and happy slaves. Although the civil rights movement dispelled the most racist aspects of this stereotype, the "romance" of the Old South maintains a hold over the popular imagination even today.

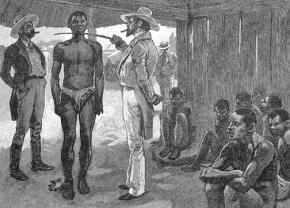

Of course, the Old South of Gone with the Wind had absolutely nothing in common with the reality of life under slavery. For the millions of African Americans who suffered under the lash of the overseer, life in the South was a waking nightmare.

Slavery--the ownership and exploitation of one person by another--is one of the oldest social relationships in human history. Slave labor built the pyramids in Egypt; it was the basis for the wealth and prestige of ancient Greece and Rome. But the form of slavery that emerged in Europe's American colonies was very different from any that had come before.

New World slavery emerged as part of the developing capitalist world economy. It was designed to produce raw materials and staple crops such as cotton, sugar and tobacco for export back to the markets of Europe.

Driven by the profit motive, American plantation owners used every means at their disposal to extract the maximum labor possible from their enslaved Black workers. As well as the whip, planters devised horrific forms of torture and intimidation to keep their slaves in line.

Bennett H. Barrow was a Louisiana planter who refused to employ an overseer due to their reputation for excessive cruelty toward the slaves. Nevertheless, the diary of even this "humane" master is full of occasions when he indulged in a "general whipping frollick," beat "every hand in the field," or attacked a particular slave and "cut him with a club in three places."

If this direct and brutal violence weren't bad enough, Black slaves had to deal with other horrors. Because they could be traded as property, many enslaved African Americans lived through the experience of having their loved ones sold away and never seen again. In order to maintain control, most slave states passed laws making it illegal for Black people to learn to read and write. Planters herded their slaves into white-run churches to hear sermons on how their enslavement was the will of God.

The first major crisis for the slave system came during the American Revolution. Not only did thousands of slaves use the chaos of the war against Britain to flee their masters, but many whites began to wonder whether a new nation supposedly built on liberty could tolerate the existence of slave labor within its borders.

Slavery had never really taken hold in the northern colonies, where climate and geography mitigated against the development of plantation agriculture. Most of these states gradually abolished slavery in the years after the revolution.

In the Southern states, though, slavery was the basis of the power of the patriot leaders. Men like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson were major slave owners, and they made sure that the new government guaranteed their right to own and exploit other human beings.

Although slavery survived the crisis of the revolutionary years, economic and social changes in the new nation drove a wedge between the free North and the slave South. Free from the control of imperial authorities, the U.S. intensified its war against American Indians, and thousands of white colonists streamed westward to settle on land stolen from the indigenous people.

At the same time, independence gave a tremendous boost to the development of an industrial and commercial economy in the Northeastern states. Soon, textile mills, railroads and canals were spreading across the free states.

Meanwhile, in the South, the genocide against the Indians allowed cotton plantations to spread from the Eastern seaboard to what we now think of as the Deep South--states like Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.

Southern planters were getting richer and stronger, but so too were those in the free states who resented slavery. Small farmers in the West feared the competition from slave labor. Northern industrialists complained that slavery impeded the spread of factories and mills, and argued with the planters over tariff policy.

Just as importantly, the Northern elite justified its own growing power with an ideology that celebrated the ability of ordinary people to rise through society and become prosperous farmers or businessmen. The South, where slaves were stuck in a perpetual state of poverty and exploitation, seemed to violate this free labor ideal.

EVEN AS some Northerners began to question the legitimacy of slavery, African Americans in the South demonstrated that they longed to be free.

Resistance could be small-scale and informal. Slaves feigned illness or pregnancy to avoid labor in the fields, or broke tools to slow down the pace of work. Sometimes individual slaves fought back when confronted with the violence of an owner or an overseer.

In his autobiography, escaped slave-turned-abolitionist leader Frederick Douglass described how, sick of beatings at the hands of an overseer named Covey, he "resolved to fight." Douglass remembered: "We were at it for nearly two hours. Covey at length let me go, puffing and blowing at a great rate, saying that if I had not resisted, he would not have whipped me half so much. The truth was that he had not whipped me at all."

Enslaved African Americans also created a culture of resistance. In the fields, they sang work songs that expressed the desire to escape from bondage. At night, when the master was in bed, they gathered to develop their own form of Christianity.

The most spectacular manifestations of resistance were the mass slave revolts that sporadically erupted in the South.

In 1800, an enslaved blacksmith named Gabriel led a slave conspiracy and insurrection in Virginia. In 1811, hundreds of slaves rose up on the plantations along the lower Mississippi River and attempted to march on New Orleans. Most famously, a Black preacher named Nat Turner organized a violent revolt in Virginia in 1831. Four years later, an alliance of American Indians, fugitive slaves, plantation hands and free Blacks made war against the U.S. Army in Florida.

None of these revolts genuinely threatened the stability of slavery in the South. Whites were always a majority, and they could count on the power of the government to crush slave rebellions. But these insurrections demonstrated that African Americans rejected their enslavement and were waiting for the right moment to throw off their chains.

The failure of the major slave rebellions showed that Southern Blacks would need powerful allies if they were to confront the planters. Starting in the 1830s, these allies began to emerge across the North in the form of abolitionist societies, the most active and militant of which were dedicated to the immediate destruction of slavery.

Runaway slaves and free Blacks formed the rank-and-file of the antislavery movement. In 1827, a group of African Americans in New York began to publish an antislavery newspaper called Freedom's Journal. They pledged to complete the revolutionary process begun in 1776, and built a network of agents and distributors to agitate for Black rights.

Newspapers like Freedom's Journal convinced radical whites to join the crusade against slavery. One such individual was William Lloyd Garrison, who founded the American Antislavery Society after coming under the influence of African American activists.

The abolitionist movement challenged many forms of oppression. The prominence of Black abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass forced many Northerners to reconsider their deeply held racism. Female abolitionists who resented the persistence of sexism in the movement became the vanguard of the struggle for women's suffrage.

BEFORE THE 1850s, however, the abolitionists remained a despised and isolated minority in the North. Powerful business interests connected the Northern elite to the planter class, and racism remained nearly universal in the free states. Many abolitionists died at the hands of pro-slavery mobs or were forced to flee their homes.

But events in the 1850s gave the abolitionists a new audience for their ideas. A national controversy erupted over whether slavery should expand into the Western territories. The United States had stolen these lands from Mexico in the expansionist war of 1846. Northern farmers and investors hoped to spread the free labor system into the West, while planters knew that slavery must expand if it was to survive in the South.

The showdown came in Kansas. Thousands of antislavery New Englanders and proslavery Missourians flooded into Kansas after 1854. Violence erupted when proslavery thugs attacked the antislavery settlement at Lawrence. In retribution, an antislavery militant named John Brown ambushed proslavery settlers at Pottowatomie Creek, killing five.

Before the events in Kansas, the two-party system had largely kept the issue of slavery out of the political arena. The two main parties, the Whigs and Democrats, had conspired to keep the slavery controversy out of Congress as far as possible. But now the facade began to crack.

A new third party, the Republican Party, grew out of the mass movement that emerged in the North in response to the crisis in Kansas. The Republicans ran their first candidate for President in 1856--pledging to prevent the spread of slavery, they captured a third of the popular vote.

Most Republicans were not abolitionists. They did not launch an immediate attack on slavery. But they did hope that restricting the spread of slavery would, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, put the institution on "a course of ultimate extinction."

Thus, when Lincoln won election as the first Republican president in 1860, the states of the Deep South had little hesitation in seceding from the Union. Even if the Republicans had pledged not to interfere with slavery directly, the planters knew their victory would encourage slave resistance and lead to the spread of abolitionist ideas in the South.

South Carolina left the Union in December 1860, and by the following June, it had been joined by 10 other Southern states. As Alexander Stephens made clear, these states seceded not to defend abstract principles like states' rights or "freedom," but to preserve the brutal system of human slavery.

When the Civil War began in April 1861 with the Confederate bombardment of Union's Fort Sumter in South Carolina, the issue of slavery again forced its way to the surface. Thousands of slaves fled to Northern lines and volunteered to fight against their former owners, and Lincoln came to realize that the North could not win without their aid. The process of war, emancipation and Reconstruction that followed would constitute the Second American Revolution.